Normal Decision Theory

do the good thing, not the decision theory thing

Decision theory is the field of study about how to define, precisely and mathematically, what “the best decision” means, when one is uncertain about the world. In modern decision theory, it’s thought that definition of “the best decision” is something of the form:

Take the action which has the best expected outcome, if you take that action.1

“Best expected outcome” is fairly well-trod ground; the von Neumann-Morgenstein utility theorem says that it’s anything that equals what would get the highest number if each outcome had a real-valued utility that was multiplied by the probability of that outcome occurring.

The main point of research in modern decision theory is, then, defining, precisely and mathematically, what “what will happen when X action is taken” means.

A “decision theory”, singular, is an attempt at a precise and mathematical definition of this. There are different “decision theories”, with different definitions of “what will happen when X action is taken”.

Why Do People Care?

Eliezer Yudkowsky, along with other people, figured out that superintelligent AI is necessary for an amazing future, but far from sufficient. In the early days of AI, we didn’t know that it seemed like you could build smarter-than-human AI without understanding cognition well. As such, Eliezer Yudkowsky studied cognition, with an eye to understanding it well enough to build smarter-than-human AI and then very quickly with the new goal of understanding it well enough to build smarter-than-human AI that doesn’t kill everyone2, and incidentally learned quite a few things about practical cognition for humans, which he compiled into the Sequences under the name rationality.

One subproblem in understanding cognition is understanding decision theory; that we don’t have a mathematical description of the optimal decision theory means that there’s something that we don’t understand about cognition, that could bite us, if we try to make a smarter-than-human AI that doesn’t kill everyone. So this is one of the topics that Eliezer Yudkowsky studied, and that his fandom (the rationality community) looked into. The Machine Intelligence Research Institute he founded published cutting-edge work on decision theory.

As a prescription for the right way to think, some found it a very compelling concept! If only you could learn the correct decision theory, then you could make all the correct decisions; and, in fact, if you make any decision that’s not the one that the correct decision theory says is best, then you’re making a suboptimal decision. And so they set out to learn decision theory (or hear enough random results of the field as they bumble around their lives).

Abnormal Decision Theory: The Pedagogy of Decision Theory

Texts that introduce decision theory as a field of inquiry have to justify why it’s a field of inquiry. Why is decision theory an unsolved field, and not like expected utility theory which was derived way back in 1945, or something even simpler, where the first equation everyone writes down is also the correct exact mathematical accounting of decisionmaking?

To make the reader truly feel this - and also to present a semi-fictionalised and cleaned-up timeline of the history of decision theory research - one way is to set up a plausible-seeming equation, and knock it down with a counterexample, and set up another one that seems plausible, and knock it down, and do that again and again until the reader understands that decision theory is hard, and has an idea of what some of the open problems are.

An introduction to decision theory, in the typical style, written by me just now:

Omega, which is very good at predicting what you will do in this scenario, approaches you with two boxes. You can take either only Box B, or Boxes A and B. Box A has $1000, and Box B has $1,000,000 iff it predicts you will only take Box B, and $0 otherwise.

Do you take Boxes A and B, or just Box B?

If your decision theory is “what happens if I take action X is the things that are caused by action X being taken”, then you reason:

Box B either has $1,000,000, or $0.

Box B already has this money in it; my decision can’t cause the amount of money to change.

If it has $1,000,000, then taking Box B gets me $1,000,000, and taking Box A+B gets me $1,100,000. If it has $0, then taking Box B gets me $0, and taking Box A+B gets me $1000

So it’s always better to get Box A+B

And so, you choose Box A+B. Omega, which is very good at predicting you, predicted this. So Box B has $0, so you get $1000.

Surprise! You only got $1000! If only you only took Box B, Omega would have predicted you’d only take Box B, and you would have got $1,000,000, so you got much less money than you could have. But didn’t “what happens if I take action X is the things that are caused by action X being taken” feel like such a natural approach that you wouldn’t have expected to be so flawed? Here’s a decision theory that would have got you $1,000,000:

(…and so on, for the holes in that decision theory…)3

This has the unfortunate side effect of making “the optimal decision theory” seem like it should be a complicated and unintuitive thing, with complicated and unintuitive results. Look at how it applies to all of these weird edge cases! Clearly, to have good decision theory is to approach the world as if it’s made of edge cases. And living in a world made of edge cases, you need to study decision theory explicitly to navigate things; your intuitions won’t do. This is a push towards people who try to reason in terms of decision theory doing crazy and unusual things; but, in fact, decision theory is very normal and natural.

Normal Decision Theory

Humans, and the cultures that they live in, already come baked in with a lot of adaptations that, together, let them act in ways that are kind of like the optimal decision theory, whatever it is. This isn’t to say that humans know decision theory;just that there are a set of motivations inside humans that, in the ancestral environment, end up with the humans acting kind of like the optimal decision theory; and a set of cultural adaptations that have developed since.

It’s only natural - decision theory is the scientific endeavour to define the best decision, and so anything that has to make good decisions to live, like humans throughout history, will come to do approximately the things that decision theory researchers discover are the best.

Humans have a sense of honor and of keeping their word.

Humans have a sense of being nice to other humans. In the prisoner’s dilemma - even the true prisoner’s dilemma - cooperate-cooperate is better than defect-defect, and so humans have an inherent drive to cooperate.

Humans have a sense of vengeance.

Humans have a sense of contributing to a collective task, and distributing the rewards from that collective task between themselves.

Humans have a sense of sometimes telling the truth, even when they can get local advantage.

Humans have a sense of sometimes following the law, even when they’re not being watched.

Humans will sometimes choose to eat meat or to keep slaves, in cases where they think those animals or those human beings won’t be able to fight back.4

These can all be described in terms of decision theory, but, importantly, they have also been done for thousands of years by people who had never studied decision theory. The optimal decision theory is normal and natural, it has always been with us since the dawn of intelligence, and you already live the parts of it that are sufficiently useful to endurance hunters in the African savanna in 250,000 BC.

Do That Which Is Good, Not That Which Is Decision-Theoretically Optimal

None of the functional adaptations above look like deriving an algorithm that resembles how the mathematical form of our best attempts at the optimal decision theory is written in textbooks, and then executing that algorithm in your head. Yet they have been optimized to hew closer to the truth than that equation has been - evolution only cares about the true decision theory, not any academic’s guess about what the true decision theory is. We haven’t solved decision theory, yet, but we and evolution live in a world where the optimal decision theory is the optimal decision theory.

Because of this, I would expect most crazy decision theory actions to also have an explanation in the ontology of mundane psychology; and I would also be suspicious of any action that one thinks follows from the mathematics of decision theory (not infinitely suspicious - evolution is fallible - but suspicious) but that doesn’t cash out in ordinary psychology. I’m sure evolution has been imperfect in giving humans decision theory! I also think it’s been pretty good.

One refuses to surrender because they have a decision-theoretic obligation to avoid acausally creating an incentive to attack them, but they should also understand that they refuse to surrender because of ordinary human pride and obstinacy. One helps out someone who helped them because they have a decision-theoretic obligation to create an incentive to help them, but they should also understand that they help out people who helped them because of ordinary human kindness and reciprocity. If the ordinary human part is missing, that’s smell that their decision-theoretic reasoning has went wrong somewhere.

Crazy decision theory actions should also have a mundane explanation in terms of just being a good idea. There are no actions that are a bad idea, and that someone also has a decision-theoretic obligation to take. If someone’s notions of a “good idea” and a “decision-theoretically optimal” idea diverge, then they are wrong about something. They might be wrong about what’s good, and they might be wrong about decision theory - even if they think they understand the mathematical formulation of decision theory, they might be wrong about how to implement an approximation to that in their own heads, or what the implications are for their own situation.

One’s notion of good is informed by one’s notion of decision-theoretically optimal; so, while they may diverge, the notion of good has more information, including being tuned by all those decision-theoretic adaptations granted by evolution. So diagnose why they differ, but if they do, I’d lean towards the good action, not the “decision-theoretically optimal” action.

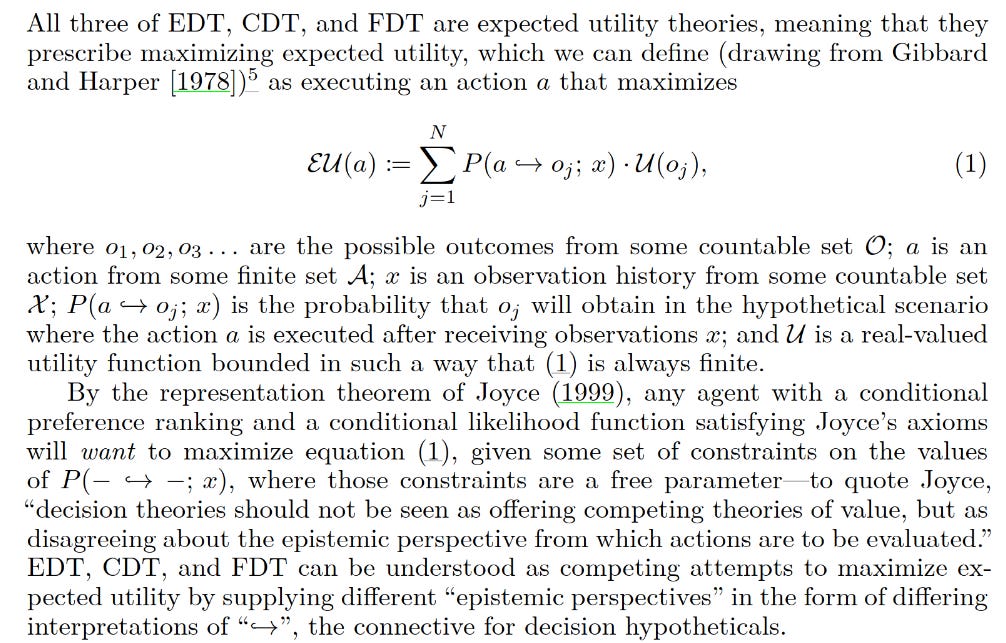

This is in words, though the goal, as I have said, is to have something precise and mathematical. The best equation is:

(Yudkowsky and Soares [2017], citing Gibbard and Harper [1978] and Joyce [1999])

I don’t just drop this equation in the quote box directly because the functional forms of and relationship between P and U already bake in a specific notion of what “the best expected outcome” means, and while that notion was solved by expected utility theory, I wanted to point that out a sentence later so as to put things in an order.

Despite the similar English name, “building smarter-than-human AI that doesn’t kill everyone” is a very different task to “building smarter-than-human AI”! As a token of the difference, it still looks like you need to understand cognition mathematically precisely to do the former, though it no longer looks like you need to understand it well to do the latter.

I’m not sure which decision theory explainer I actually used, for those who haven’t already been introduced to the field. Decision Theories: A Less Wrong Primer seems a popular albeit old post.

Decision theory is not morality and does not give you morality. Many aspects of morality can be derived from decision theory, because a sense of morality is one of the adaptations that evolution used to cause humans to approximate the optimal decision theory in their ancestral environment. Those results from decision theory that we think are moral make up a kind of Natural Law, that applies to everyone and every interaction, regardless of whether they like the person they’re talking to. If people with blue hair don’t consider people with red hair as moral patients, they still lose if they diverge from the optimal decision theory.

patch notes: added another paragraph to the "why people care" section tying EY to decision theory research in particular

Following the math can lead you to some important truths, but only to the extent that you really understand math.

While reading autopsies of FTX, I was often struck by accounts of how SBF would justify decisions in terms of expected value calculations made with numbers pulled out of his head. EV calculations can be useful, they're the main reason I send more money to GiveWell than to my local community centers, but they're also a pretty basic way to think about probability. An obvious problem is that if pressing a button has a 60% chance to double your money and a 40% chance to take all of it, pressing the button has a higher EV than not pressing it and yet if you keep doing this you will inevitably end with $0. You need a more detailed understanding of probability and general business sense to guide a multi-billion financial firm, and yet he explicitly said he was just using crude EV calculations all the time, and the people who worked for him did not see a problem with this!